Report by Carmel Eilon with her photographs of the event

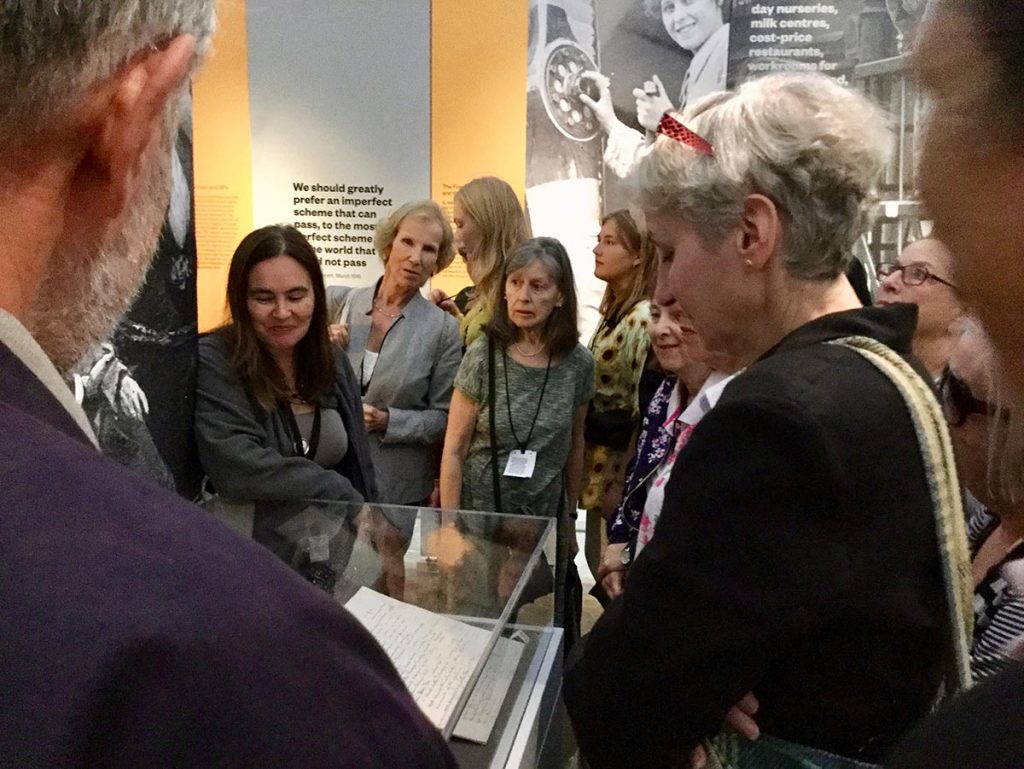

On Monday 17 September 2018 Daphne Berkovi took a group of U3A ”students” to the Houses of Parliament where she had arranged for Dr Mari Takayanagi to take us on a guided tour of the Vote100 Exhibition of Women’s Place in in Parliament.

Dr Takayanagi, who had co-curated this exhibition along with Melanie Unwin, explained it celebrates the 100 year anniversary since some women and all men were first entitled to vote in Britain. The exhibition, accompanied by fascinating photographs and documents and explanatory texts was divided into four sections.

The first area, The Ventilator, covered the period 1818–1834, when women were not only forbidden to vote but also not allowed to enter the public galleries to watch the proceedings. Well born ladies, usually relatives or friends of the sitting MPs, found an attic space above the chandeliers in the chamber where they could stick their necks through ventilation holes to hear and get a bird’s eye view of politics in action. Drawings from this period by Lady Georgiana Chatterton and Frances Rickman show this octagonal structure and a partial mock-up allows visitors to participate in the experience.

From 1850 the Ventilator was replaced by The Cage. The “new” Palace of Westminster included a purpose-built Ladies’ Gallery so until 1918 women were permitted to peer over the balcony in this enclosed cell-like structure and watch debates through the heavy metal grilles covering the windows. The grilles were constructed to ensure the male MPs below were not distracted by the sight of the ladies above. Meanwhile, as illustrated in Harry Furniss’ sketches and the reconstructed Cage, this area was hot, stuffy and had a poor view of the proceedings. Nevertheless women demonstrated increasing interest in politics, using their network of family and friends to gather 1500 signatures from across Britain to the first mass women’s suffrage petition in 1866, a major achievement in pre-internet days. John Stuart Mill MP (step-father to the feminist campaigner Helen Taylor) who presented this petition to the House said “to say the least (this) greatly weakened the chief practical argument which we have been accustomed to hear against any proposal to admit women to the electoral franchises — namely, that few, if any, women desire it”

Displays of Millicent Fawcett and the Suffragists versus Emmeleine Pankhurst and the Suffragettes explained the different campaigns. The exhibition also included the growing number of men to support women’s enfranchisement, such as George Lansbury MP and Israel Zangwill. Personally I had not realised the sacrifices made by some of the “Suffragettes in trousers”, like Frederick Pethick Lawrence who — together with his wife Emmeline — was imprisoned and forcibly fed. Coverage of the anti-suffrage movements, who strongly believed political activism de-feminised women who should not seek equality but instead concentrate on their different responsibility of caring, being maternal and undertaking practical domesticity.

The first woman MP, Constance Markievicz was elected in 1918 but, as an Irish Republican, refused to take her Westminster seat. The first woman MP to sit in House of Commons was Nancy Astor who was allowed access to the new Ladies Members’ Room. Amongst other items on display was her plain black outfit, similar to a man’s suit, which she designed especially because she wanted people to judge on what she said, rather than on what she wore. Viscountess Astor was joined in this room by other pioneering women from all parties, as this was the only place they were allowed to use, whatever their political connections, it soon became cramped and was nicknamed The Tomb. Sitting in the reconstructed room demonstrated to us the insufficient facilities, even chairs!

In showing how far we have reached, the Wall of Names listing all 419 women MPs chronologically shows most were elected since 1997, to the current level of 25% representation. Also noteworthy, despite women like Viscountess Rhondda campaigning in 1918 for women to be allowed to sit in the House of Lords, it was only in 1958 that women were accepted, and then only appointed as Life Peers, and only in 1963 Peerages Act were both men and women allowed equality as hereditary peers.

Dr Takayanagi was brilliant, explaining the context as well recounting many background stories — such as Emily Wilding Davison who hid in a broom cupboard so she could record the House of Commons and how Tony Benn installed a plaque on the cupboard door; how they found the original bolt clippers used to release the bolt and chain when women secured themselves to the Cage grilles; the petition being hidden in an apple cart and many other fascinating tales. An interesting and informative day — much enjoyed by us all.